Title |

FAQs |

Author |

|

Date |

What is publishing?

Is it a professional field, an activity, a function, a button, a phase or a specific moment in the life of publications? Is publishing all these things at once?

People like Clay Shirky provide a reductionist idea of publishing that derives from the older truism according to which “everyone is a publisher”:

Anyone with a modem is potentially a global pamphleteer (Markoff 1995).

Clearly, this is a technology-oriented perspective. But not everyone agrees that everyone is a publisher. In fact, people like James Bridle (2011) defend the skills of publishers as social agents:

Contrary to popular thought, everyone is not a publisher. When you hear a publisher say it, it’s even sadder. Publishing is a complex and well established collection of knowledge, competencies and processes, refined over time, practiced under forever difficult circumstances in a frankly indifferent market.

Frequently, people define publishing as ”making things public”. According to Michael Bhaskar (2013) this definition is too abstract to be somehow useful. Is dropping some content on a website that isn’t visited by anyone sufficient to make something public? Bhaskar prefers to speak of amplification, a process that requires ”a movement from lesser to greater exposure.”

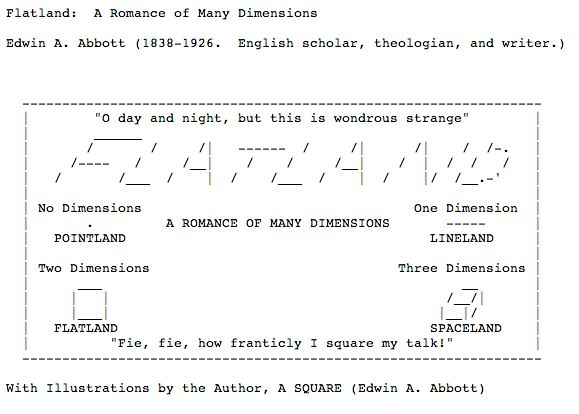

In a similar vein, Matthew Stadler (2010) of Publication Studio proposes a shift from publishing to publication, meaning with the latter “the creation of a public.”

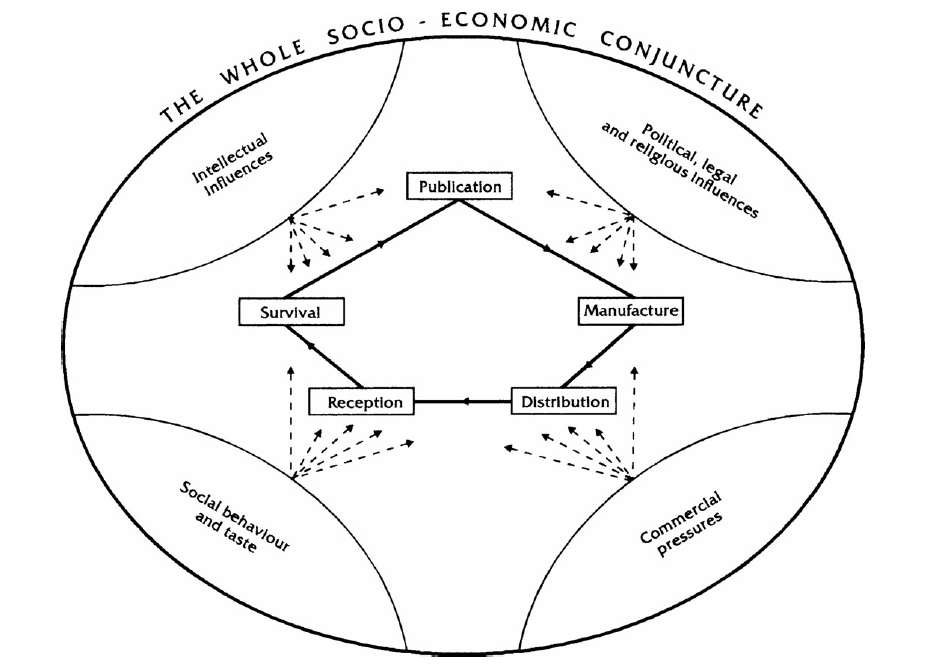

Publishing can also be understood in a processual way, that is as a series of phases. This is the case of Adams and Barker’s (1993) model, developed in the context of book history. According to the scholars,

the decision to publish, not the creation of a text, is […] the first step in the creation of a book.

Here we see the glimpse of an interesting idea: the idea that publishing comes before writing. Rachel Malik (2008) expands this idea by maintaining that

publishing precedes writing and governs the possibilities of reading.

That’s why she refers to the “horizons of the *publishable*” as a way to identify the constraints to what is actually writable, distributable, and readable.

I like this notion because it shows how publishing begins before writing and doesn’t finish after distribution. It also highlights mediation by focusing on how each process is regulated at multiple levels.

Related: Mood Disorder, David Horvitz, 2015.

How does digital technology relate to publishing?

From my point of view, ‘digital’ can have three meanings:

Technically, ‘digital’ means encoded in discrete units. Therefore, digital data can be expressed as 0s and 1s, but also as beads in an abacus or as the tiles of a mosaic.

Then, there’s a colloquial meaning that corresponds to networked electronic devices and the infrastructure they employ: laptops, mobiles, ebook readers, and the internet.

Finally, there is a rhetorical understanding of digital as a ”way of being” epitomized by Negroponte’s 1995 book Being Digital.

When it comes to publishing, these understandings of digital are deeply intertwined. Digital devices became a symbol and a means of collaboration, openness, immediacy, and, ultimately, progress.

I believe that experimenting with the technical understanding of digital data might help us to rethink the other ones. Experimenting, for instance, with non-electronic supports to store digital information might lead us to question the propaganda around innovation.

Related: SKOR Codex, La Société Anonyme, 2012.

So do you prefer to speak of e-publishing?

Only if the ‘e‘ stands for ‘ersatz’. Honestly, I’m more interested in the cases in which electronic devices represent a deficient surrogate of traditional ways to create and distribute content.

Let’s consider this ebooks-only Texas library. Basically, the library of the future looks like an Apple Store. This kind of library is probably cheaper than the ones with physical books but it is a surrogate in several ways: no guarantee of privacy, an interaction with books that is regulated by the specific software provided by one company, and so on.

I remember Geert Lovink saying that the physical library will soon be a luxury. Unfortunately I think he’s right.

Related: Bibliotecha, 2013-present.

In the age of digital computers, is there still materiality?

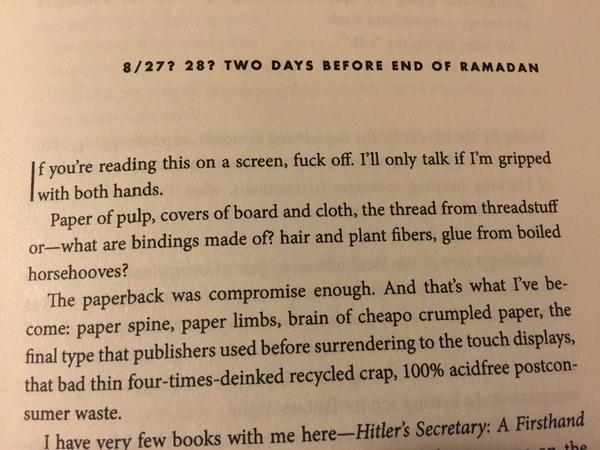

Digital technology is not immaterial, at least no less material than, for instance, printed matter. And as can you see in the incipit of Joshua Cohen’s Book of Numbers, the materiality of electronic devices can even be addressed in negative terms.

My favorite account of the computer’s materiality comes from N. Katherine Hayles (2004). In her words, “digital computers have an Oreo cookie–like structure with an analogue bottom, a frothy digital middle, and an analogue top.” So there’s no digital without analogue.

As Johanna Drucker points out, materiality is a performative features of artifacts: “what something is has to be understood in terms of what it *does*”. This type of performativity can be fruitfully exploited by artists and designers alike.

Related: C.O.P.Y, Martin Wecke, 2013.

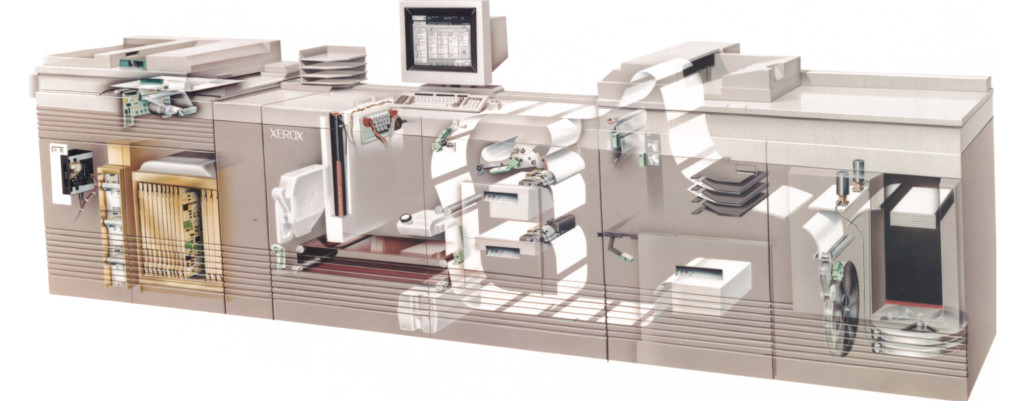

Why there’s so many Print on Demand books on P—DPA?

Because POD books represent a genuine hybrid of digital and analog processes: under the guise of the ‘traditional’ book form, there is a complex ecosystem made of file formats, metadata, retail platforms, multiple connections to online stores and, sometimes, even YouTube book trailers, authors’ blogs, etc. Sent through the regular postal system, the physical book is the tip of the iceberg of an infrastructure that takes advantage of digital printing, desktop publishing, PDF format, and Web 2.0. Therefore, POD is not a new technology in itself, but a fruitful combination of existing ones.

Related: Black Book, Jean Keller, 2013.

Is this ‘post-digital’?

Post-digital is — actually, was — a buzzword. Post-digital shouldn’t be understood as ”after the digital”. As Florian Cramer (2014) suggests, the ‘post’ attribute is used as in ‘post-modern’ or ‘post-industrial’. Thus, it points to the idea of a crisis of digitality.

Often the term is used to refer to neo-analog, retro artifacts or to artifacts that mix the features of the so-called new media with old media ones. Even though admittedly generic and diluted, my understanding of ‘post-digital’ is aligned to the ideas of Siegfried Zielinski (2014):

Working consciously ‘post-digital’ cannot mean to work without digitality. Digital tools, instruments and systems are surrounding us and are inherent for our cultural production and perception. To work beyond digitality — as an ideology and a hegemonial practice — means to reach beyond the glossy surface effects the digital is able to organise.

So, I believe that blending old and new technologies is not a requirement of a post-digital attitude. This becomes interesting only when a gesture is able to reach beyond digitality as ideology.

Related: E-Book Backup, Jesse England, 2012.

But then what is ‘experimental’ and what is not?

According to designer and publisher Peter Biľak (2005), in the field of design

Very few terms have been used so habitually and carelessly as the word ‘experiment’.

I think he’s right. My impression is that in the field of publishing the goal of experimental projects has mostly been to overcome the financial and identity crisis of the sector.

Every major player is experimenting with new technologies in order to be still relevant in the next 510 years. From VR to algorithmic writing, experimentation seems driven by FOMO.

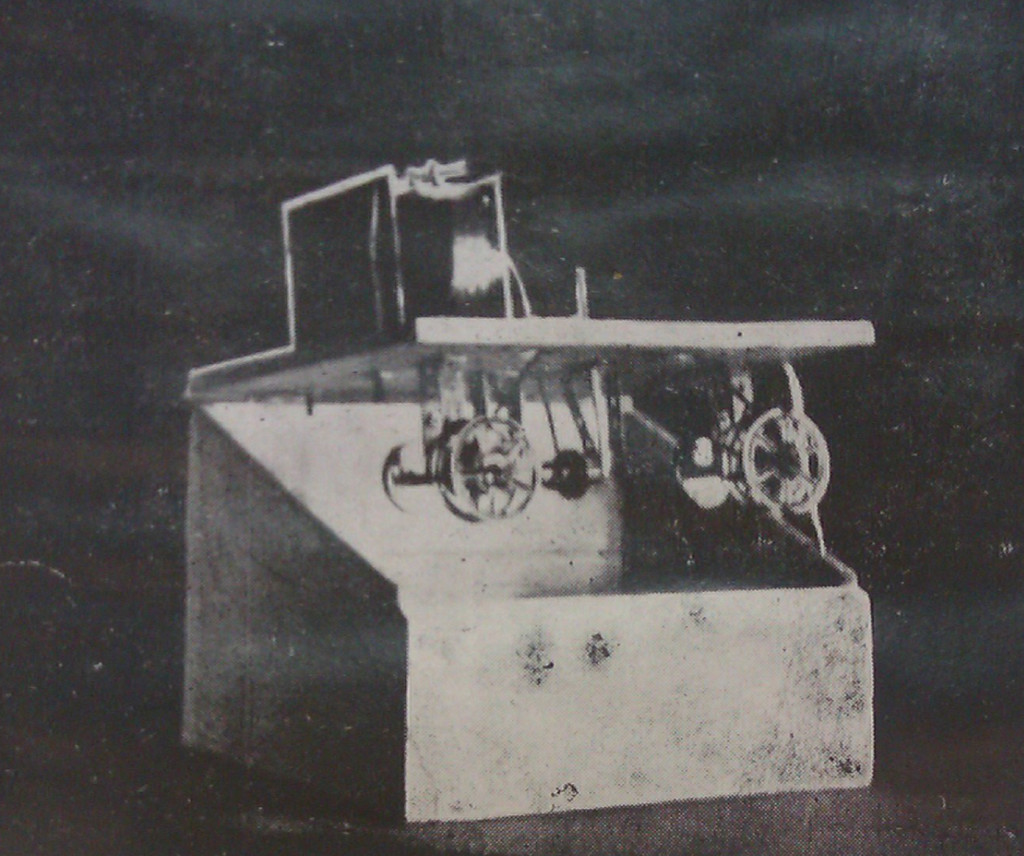

Bob Brown’s reading machine (1930s)

In my perspective, experimental publishing is something different. I’d say it resonates with avantgardistic attempts to push the boundaries of their medium of choice. The problem is that nowadays pushing the medium’s boundaries is the very dominant attitude.

So, in my opinion, a genuinely experimental practice requires:

- a practical, hands-on approach in which making produces meaning;

- an (inexorably impermanent) antagonism towards the mediating forces of the hegemonic discourse.

Similarly, Alessandro Ludovico (2012) lists the following requirements to create an ‘alternative publication’.

[…] to challenge the prevailing medium, to formulate a new original aesthetic based on the new medium’s qualities, and to generate content which is relevant to the contemporary situation.

Related: The DRM Chair, Les Sugus, 2013.

What about ‘rich media’ publications like enhanced books?

I have nothing against them, but I find that most of the times their use of interactivity and multimedia is ‘ornamental’. The inclusion of videos, audio files, and dynamic content seems a means to justify the technology, and in doing so, these publications reconfirm an hegemonic idea of digitality as intrinsically valuable.

Take, for instance, Facebook Instant Articles. Publishers are bargaining their editorial freedom for autoplay videos, interactive maps, and instant load.

There are exceptions though: sometimes this ornamental use of widgets and tools represents a strategy to highlight standardization and to exploit it in an ambiguous way.

Related: Natural Gestures, Silvio Lorusso, 2015.

Are there ‘poor media’ publications as well?

Of course. TXT, PDFs, and PDFs can all be considered poor media. Similarly, tools like markdown are poor media since they foster duplication and boost circulation. More than a technical concept, ‘poor media’ is an attitude characterized by the conscious, serene renunciation of embellishments in favor of accessibility and spread.

Here’s a tentative list of poor media’s features:

- poor media foster duplication and boost circulation;

- poor media are lightweight;

- poor media suggest an active use: converted, dissected, remixed, reorganized, updated;

- poor media encourage preservation: “lots of copies keep stuff safe”.

Related: Adobe PDF, Patrick Armstrong, 2010.

Nowadays, many different terms — such as archiving, collecting, storing, preserving – seems to conflate. This is because archiving is a default process inseparable from any computer activity. Think of the autosave function or the browser cache.

Archiving is still my favorite term because it has a sort of institutional aura and it brings to the fore the power relationships it implies: the inclusion of an item in the archive presupposes that some other ones are excluded.

According to philosopher Yuk Hui (2014), the job of an archivist is to create context. If we adopt this simple definition, we realize that archiving doesn’t require the acquisition of physical objects or rare items.

The work of Paola Antonelli, design curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, is emblematic in this sense. Under her guidance, classic videogames like Pac-Man or ordinary artifacts like the ‘@’ symbol became part of the permanent collection.

Related: Internet Cache Self Portrait, Evan Roth, 2014

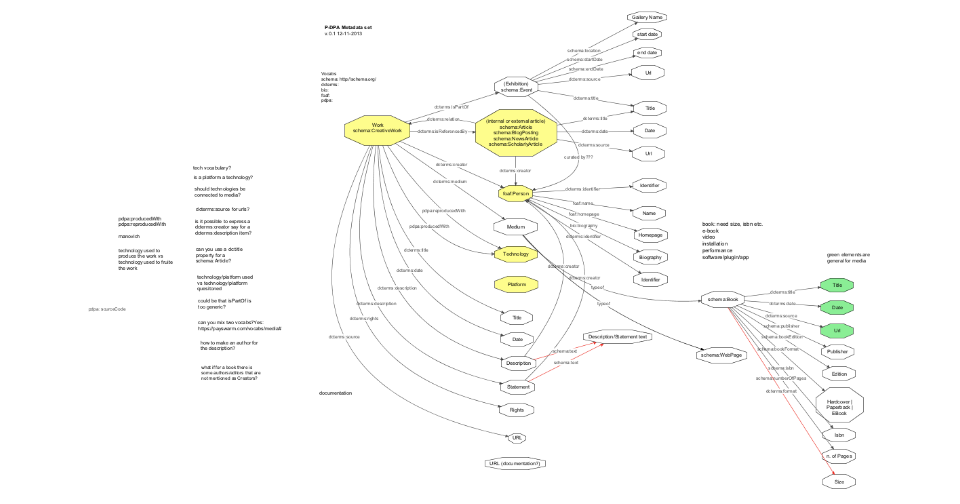

How do you categorize the works?

Categorization is a powerful way to create context around cultural artifacts. That said, I must admit that the categorization system I adopt on P—DPA is pretty naïve and by no means scientific. Above you see my failed attempt to design a rational comprehensive scheme. After that, I tried to simplify and now I have three main categories:

- media — the carriers of the work, with the exception of performances: from animated GIFs to mugs;

- technologies — the technologies that are needed to create, use, and replicate the work: from programming languages like JavaScript to mini-computers as the Raspberry Pi. This part is particularly flawed since it is difficult to identify what is not a technology, e.g. the book or the alphabet itself;

- platforms — these are what matters the most nowadays. Many of the works included in P—DPA address the operations of proprietary platforms. So it is crucial to take trace of them and to explain their relationship to the works.

Related: Books Scapes, Julien Levesque, 2012.

Is excellence your main inclusion criteria?

Not really. Several works in the archive aren’t masterpieces. But I’m not worried about that, since I’m more interested in the techniques adopted and the issues raised rather than the execution of the work.

Many works in the archive were developed during workshops or university courses. These are the contexts in which a truly experimental practice can take place. These are protected spaces in which it is possible to address unsolved issues regarding the creation, distribution, and reception of knowledge without having to submit to the needs of the market and therefore without replicating its narrative.

I also try not to privilege the first work employing a specific technique. In this way it is possible to build some micro-histories related to a specific tactic or issue.

Related: Printing Wikipedia — A Chronology, 2015.

Does P—DPA serve any purpose other than ‘creating context’?

Hopefully, it will function as a ‘generative’ resource, able to foster the imagination of new works and experiments.

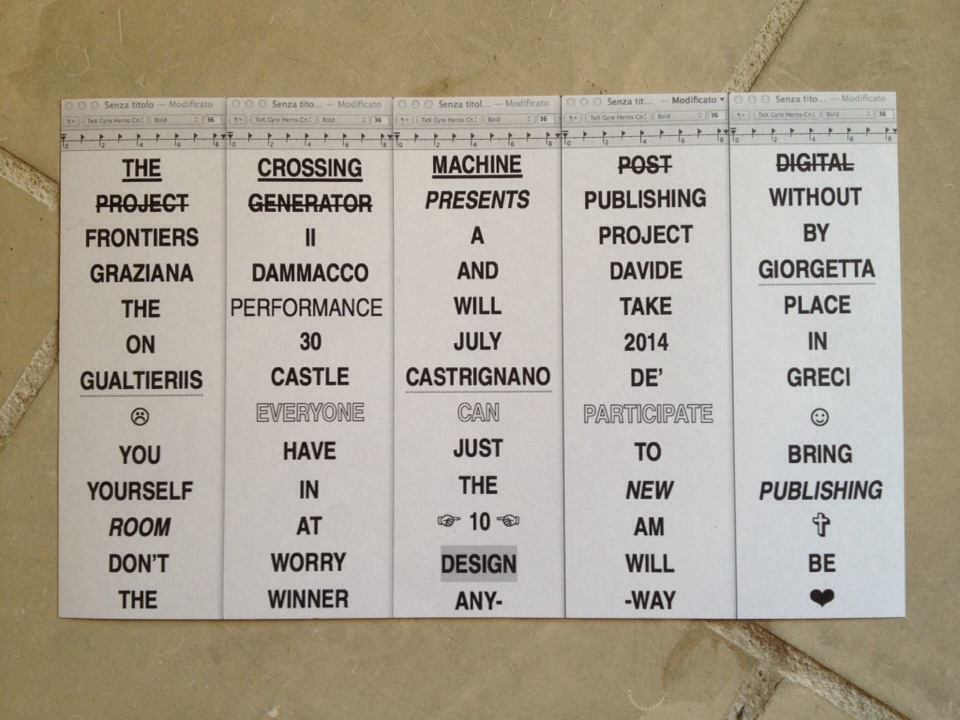

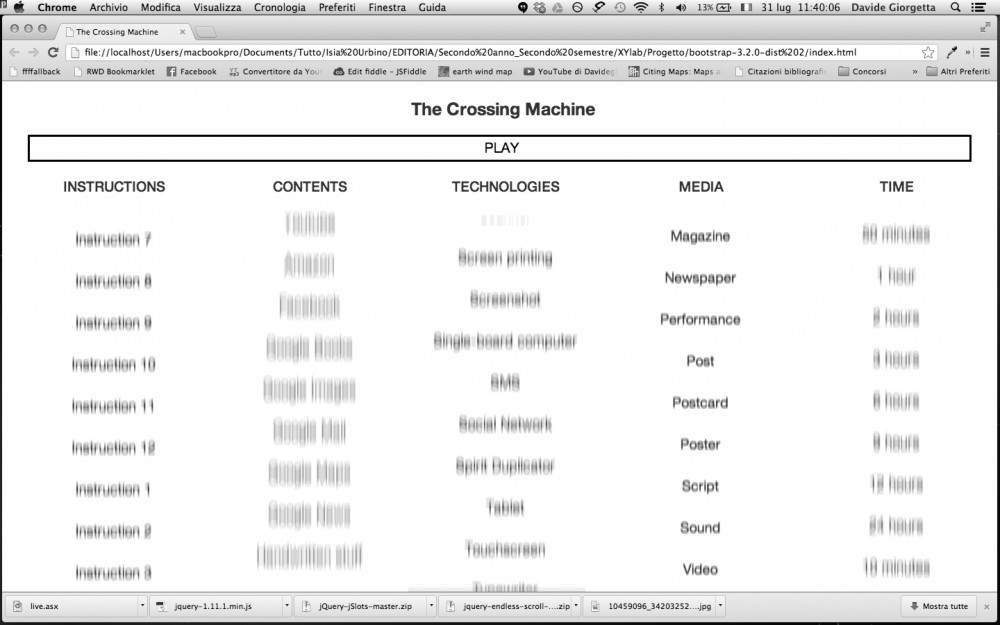

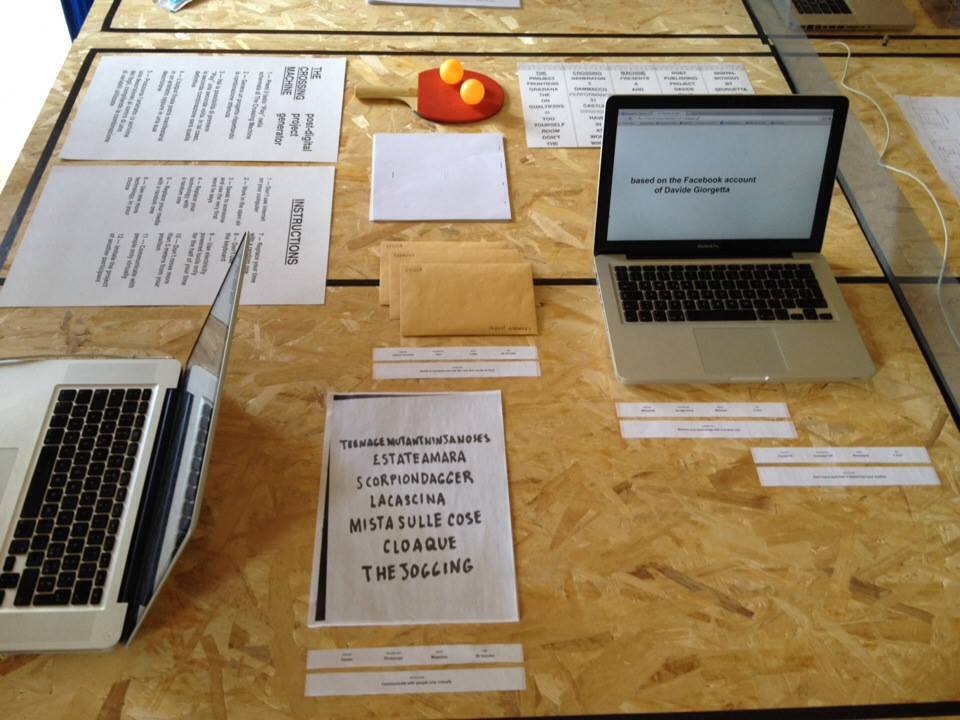

A proof of concept of this attitude emerged during XYLab summer school. The Crossing Machine by Graziana Dammacco and Davide Giorgetta derived from the discussions about the notion of innovation through different media. Their online slot machine provides instructions to create projects and artworks.

During a performance, the group actually tested the machine by developing a series of projects that involved, among others, Yahoo Answers, Tumblr, and copy-machines. The project was inspired by P—DPA’s index page, where the listed categories became a selection of operative strategies.

What are your inspirations?

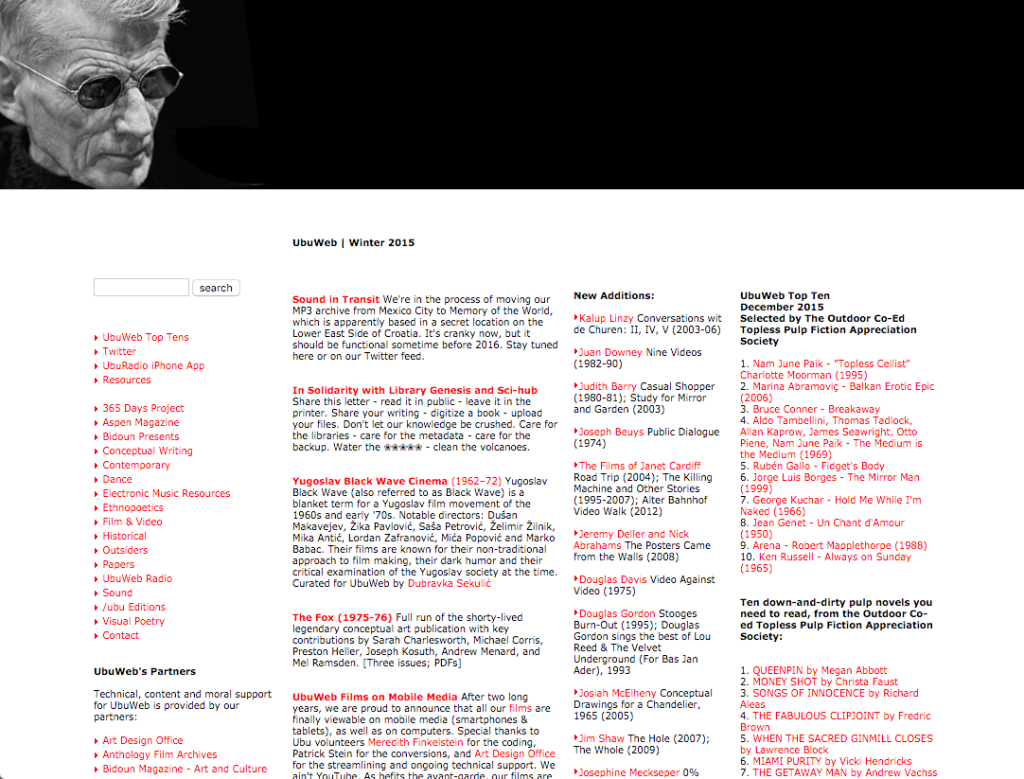

Many. If I had to choose one, it would be UbuWeb, an online archive of avant-garde works founded in 1996 by Kenneth Goldsmith.

What I like the most of it is the simplicity of its infrastructure (no CMS, no databases) and how resilient it proved to be despite its fragility:

UbuWeb is a flat HTML 1.0 site. There is no programming behind it, absolutely everything is written in BBedit by hand. You know I want to keep the site very basic, because what really is new is this radical sense of distribution (Goldsmith 2007).

Is P—DPA somehow biased?

Absolutely. At the moment, every included work comes from European countries or the USA. This is something I’d like to fix.

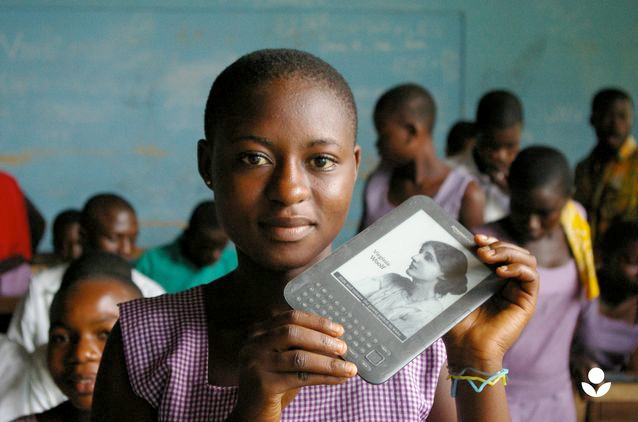

For instance, there have been many projects led by rich countries with the goal of fostering literacy in developing countries. One of these is the Worldreader program.

Without questioning the value of these initiatives — even though I think that suspicions about techno-cultural colonialism are legitimate, I’m sure that there are out there grassroots projects envisioned and developed by the very denizens of these countries.

[These FAQs were presented for the first time as a lecture at the Eady Forum of the Royal College of Art, London (UK)]