Title |

Digital Publishing in the Age of Platform-Centricity |

Author |

|

Date |

[Transcript of the talk given on October 29th during RWX (Read/Write/eXecute): a three-day worksession and public talks programme curated by Dave Young.]

Hello everyone, I’m glad to be here and I’d like to thank Dave Young for providing such a sharp framework to this compelling event. In fact, my intervention will be a sort of response to his introductory text, entitled “Know Your Filesystem”.

According to Dave, “we — as users — are experiencing a shift in the way digital data is represented and accessed.” One of the crucial aspects of this shift — Dave continues — “is that the ‘traditional’ filesystem interface, familiar to us as a visually traversable hierarchical structure of files and folders, is replaced by an app-centric interface that, with its primary objective of being more user-friendly, limits as much as possible the tedious and touchscreen-hostile tasks of file management and directory navigation”. Dave’s main argument is that this seamless, and supposedly ’frictionless’ interface has the side effect of removing “options, alternatives, and [therefore] user-agency”.

His claim highly resonates with some of the ideas I expressed in an essay entitled “Digital Publishing: In Defense of Poor Media”, therefore I’ll take this chance to expand on that. While Dave’s object of analysis is the filesystem, I focused on how digital publications are accessed and what kind of operations they suggest or allow.

The title of my essay was an homage to German artist and writer Hito Steyerl who, in 2009, described the kind of “charge” that the poor image — an image that “has been uploaded, downloaded, shared, reformatted, and reedited” — acquires while circulating through networks. I argued that in the field of digital publishing, poor media are able to “transform quality into accessibility,” like the poor image does. So what do I specifically mean by rich and poor media?

Rich media is a generic term I use to indicate a series of paradigms — reflected in both hardware and software — that foster a consumer-oriented use of publications, and in which features commonly identified with digital technology like multimediality, interactivity, and dynamicity are often mostly ornamental. They function as special effects.

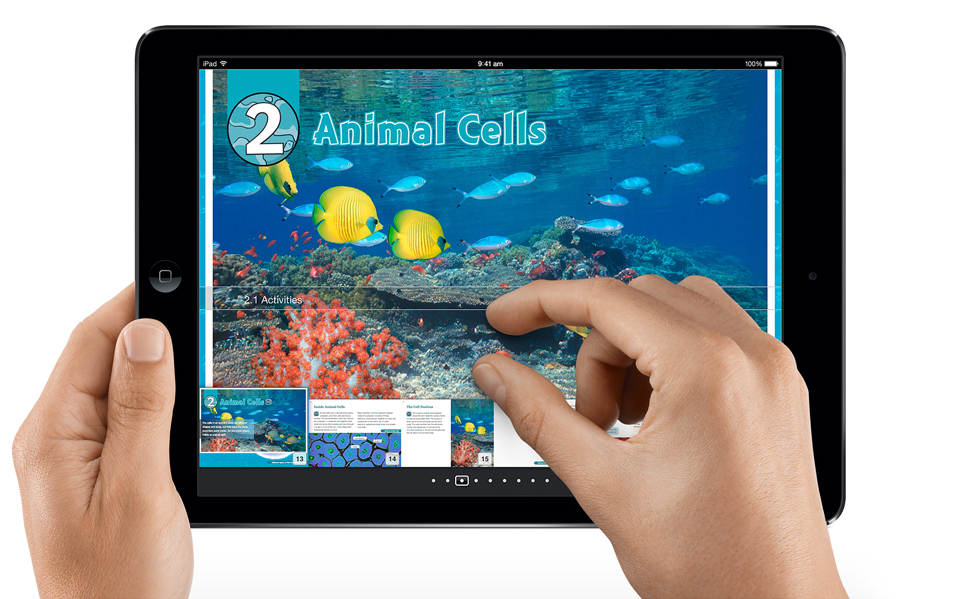

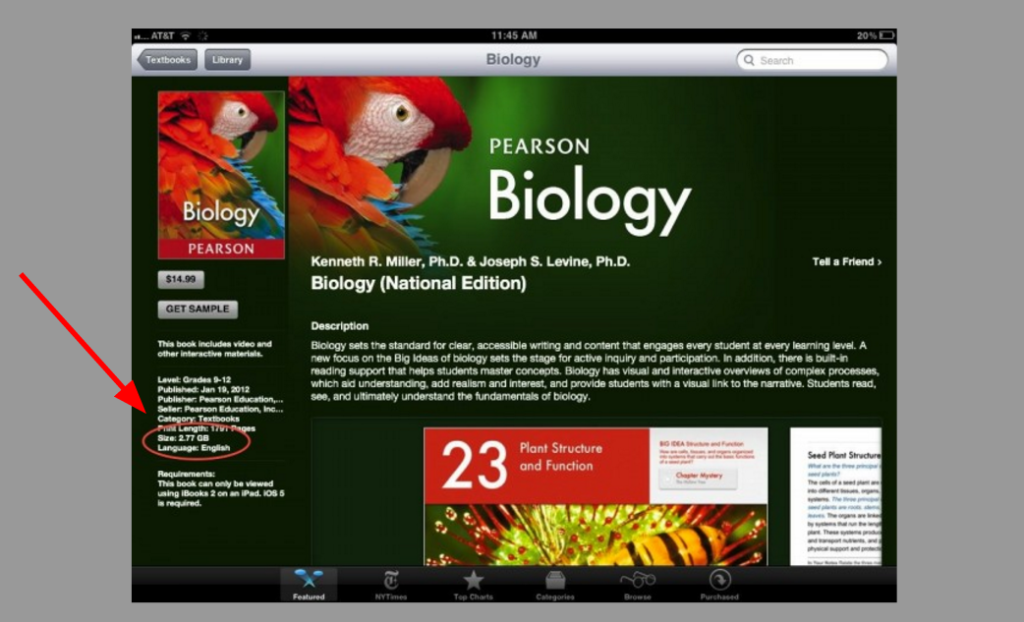

An ebook made with iBooks Author. Source: https://www.apple.com/education/ipad/ibooks-textbooks/

In this regard, enhanced ebooks and book-as-apps are emblematic. Let’s consider, for instance, Apple’s iBooks Author, a software to create ebooks that can include “galleries, video, interactive diagrams, 3D objects, mathematical expressions and more”. These books are what publishers, designers, and readers often think of when asked about the ‘future of the book’, ignoring the fact that they represent a small, barely lucrative, slice of the overall production of ebooks.

A typical example of digital publishing commercial parlance, 2015. Source: http://publishingperspectives.com/2015/03/is-metabook-the-next-evolution-of-the-book/

The fact that access is prescribed by a single tool and the consequent removal of ”user-agency”, typical of an app-centric environment, becomes evident here. For example, sometimes you get fancy HD videos, but you’re not even allowed to copy-paste the text of the book.

A typical example of digital publishing commercial parlance, 2015. Source: http://publishingperspectives.com/2015/03/is-metabook-the-next-evolution-of-the-book/

Speaking of user-agency, an aspect that is particularly relevant to me is the narrow-minded inclusion of ’social reading’ functionalities. In the app-centric paradigm, ‘social reading’ often merely means to have a button to share passages on Twitter and Facebook. This perspective betrays OpenBookmarks’ definition of social reading which corresponds to "everything that surrounds the experience of reading electronic books (ebooks).” This definition encompasses, among others, the following situation:

You’re reading a book on one device, but half-way through you switch to another ereader. Your position and bookmarks are automatically synchronised.

Enhanced ebooks do not fully allow this. Yes, you can read the book on several devices, but you cannot extract it from the monolithic ecosystem in which it is sold and reproduced. App-centricity thus means ecosystem- or platform-centricity. Of course this condition paves the way to censorship and control, as Geometric Porn, a game app rejected by both Apple and Google, shows.

Also, in a more concrete sense, the platform-centricity of rich media indirectly increases the so-called ‘digital divide’. Again, if we look at Apple iBooks’ most popular textbooks, we realize that the average size is around 1Gb. Accessing these publications means owning a capacious device connected to a pretty fast Wifi. In this sense, rich media reflect the privileges of rich countries.

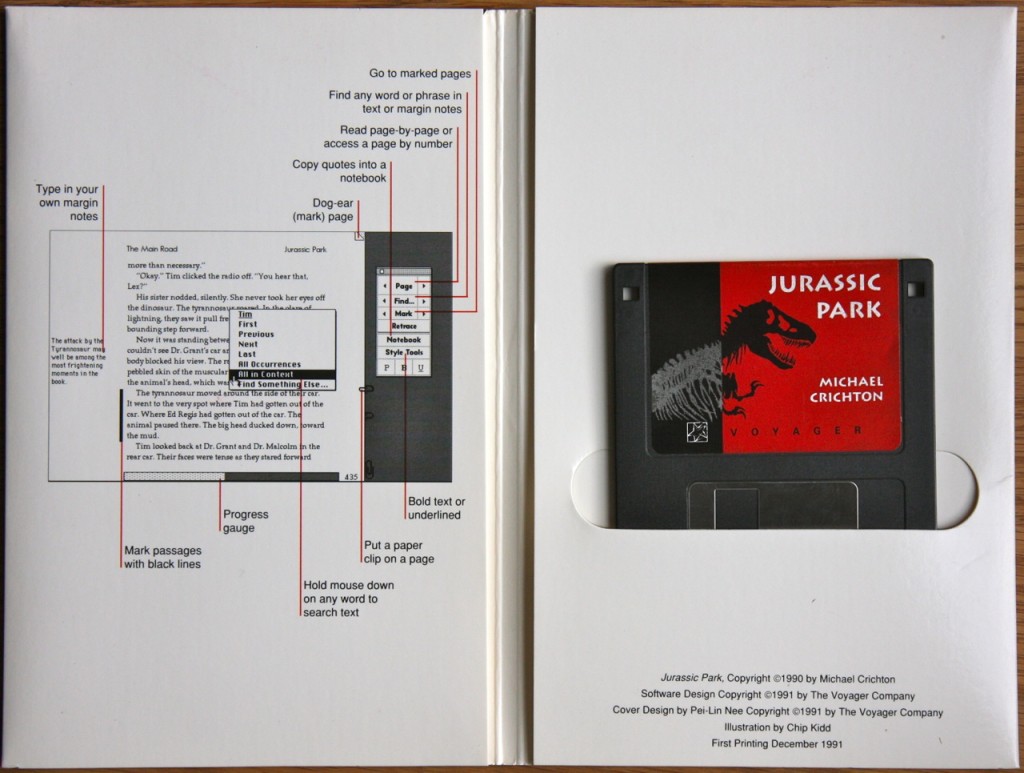

A closer look reveals that app-centricity in ebooks is not something new. In a way, the interactive CD-ROMs of the 90’s weren’t dissimilar from contemporary enhanced books. During an episode of the Computer Chronicles from 1993, ebook pioneer Bob Stein presents some of the products of his Voyager Company, founded in 1985.

I find the anchorman’s reaction particularly interesting: he doesn’t seem totally satisfied with the product and repeatedly asks for graphics. I find this short excerpt representative for the kind of inferiority complex toward printed books that early ebooks suffered from. Multimedia was the cure: video and audio made ebooks unique and more captivating than printed matter.

Jurassic Park Expanded Book, Voyager Company, 1991. Source: http://alfabravo.com/2011/08/early-ebooks-and-why-they-failed/

In a way, these early ebooks were app-oriented, since such functionalities as full-text search or annotations were embedded into the book program itself. Maybe it made sense at the time because there wasn’t any proper general-purpose software. But still, why would you copy quotes in a app-based “notebook” instead of a simple text file on your computer?

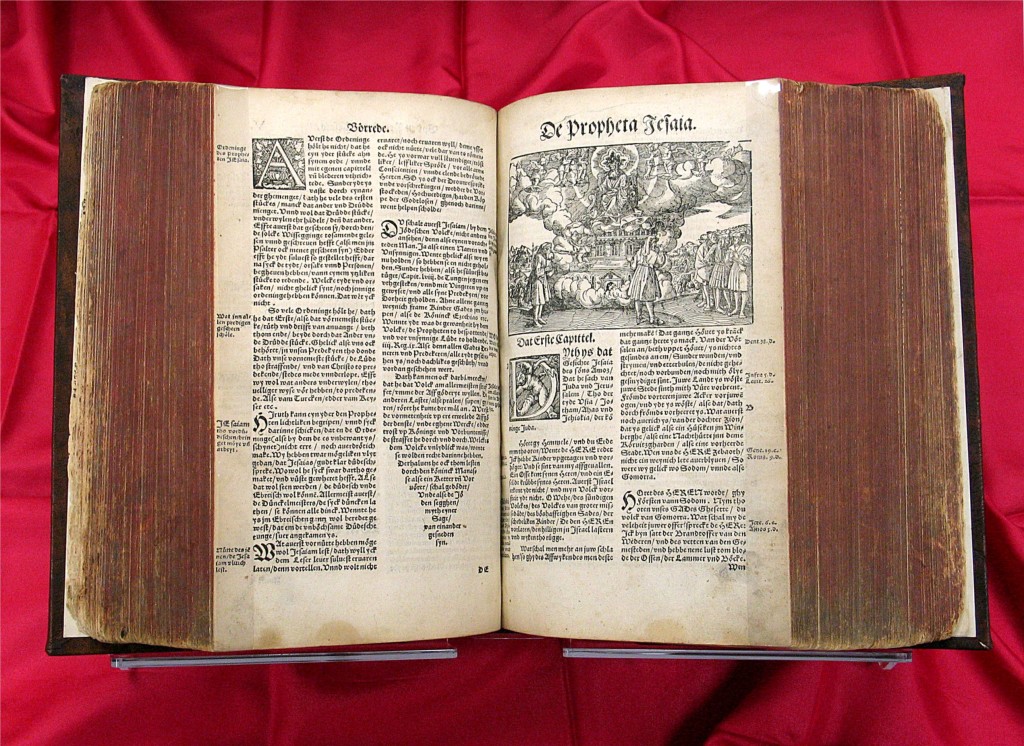

Luther Bible, 1545. Source: http://library.dts.edu/Pages/TL/Special/sc_bibles.shtml

Rich media emphasize the characteristics of the book as a technology to be used and consumed and, in doing this, they advocate for quality as visual appearance. On the contrary, poor media express and corroborate the book’s potential of duplication and dissemination. This attitude, too, has a long tradition: the whole history of the book, not just since the advent of digital networks, can be understood as the sacrifice of a certain idea of material quality in favor of a faster duplication or a broader reach. The above Luther Bible, definitely not as fancy as monks’ hand-illuminated one, is a good example.

Xerox Sigma V mainframe computer. Source: https://ediebresler.wordpress.com/2011/09/09/long-live-the-e-book/

An episode that well exemplifies poor media is the birth and evolution of Project Gutenberg. In 1971, during the night of the fourth of July, Michael Hart, at the time a Human-Machine Interfaces’ student at the University of Illinois, used the time available at the mainframe computer of his university (time that was worth millions of dollars) to retype and publicly distribute the text of the United States Declaration of Independence. At a time in which computers were mainly used for data processing, employing them for content distribution was not an obvious choice.

In Hart’s words, “the greatest value created by computers would not be computing, but would be the storage, retrieval, and searching of what was stored in our libraries.”

This attitude, together with the adoption of “Plain Vanilla ASCII,” a universally interchangeable standard for text, led to the development of Project Gutenberg, a volunteer-based platform whose mission is to “encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks”. All the books on Project Gutenberg are in the public domain and freely available for download.

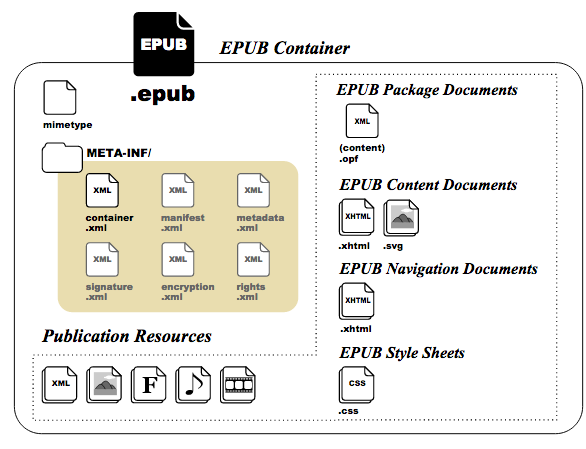

Currently, Project Gutenberg also includes books in HTML and EPUB format, a free and open standard for digital books. EPUB 3, its latest release, may include audio, video, and interactive elements programmed in Javascript. Despite this, I consider EPUB a poor medium. The reason is because its inner architecture is crystal clear and easily accessible. An EPUB book is basically a portable website: a compressed series of HTML and CSS files together with metadata and structure.

In his text, Dave denounces the fact that users can’t see the filesystem anymore. Something similar happens with app-centric books: in this case, it is the structure of the publication that becomes hidden or rather crystallized in the way the app configures it. EPUB, on the contrary, is flexible and potentially transformative. As a little demonstration, I’d like to show you a proof of concept I realized together with Michael Murtaugh, Miriam Rasch, and Kimmy Spreeuwenberg in the context of the Digital Publishing Toolkit project.

The idea was rather simple: to use EPUBs not as an output but as a source. To do so, we wrote a little script that gathers all metadata and images from the publication and compiles them into an “ebook trailer” as animated gif.

In order to compare the different filesystem interfaces, Dave uses the category of “mediation”. From this perspective, the Terminal happens to be the most ’immediate’ one. To me, mediation is nowadays the most crucial aspect of publishing. This is because the field is permeated by an idealistic narrative of autonomy and independence, epitomized by terms such as ‘self-publishing’ and ‘disintermediation’. Such rhetoric seems a repetition of the big claims that were made when the Internet became mainstream. As early as 1995, according to the New York Times ”anyone with a modem [was] potentially a global pamphleteer”.

Mediation, tough, is more present and powerful than ever: with things like the recent Facebook’s Instant Articles, multimedia articles directly hosted on Facebook, that we witness the surrender of big newspapers to the pervasive mediation of the social network, for the sake of content that is “interactive and immersive”. We witness rich media hypnosis.

Since 2013, I’ve been running an online archive of experimental publishing informed by digital technology called P—DPA, which stands for Post-Digital Publishing Archive. I collected several works according to my shifting interests within the immense universe of publishing. But now, after a couple of years, I see a dominant theme emerging: the materialization, exploitation, and subversion of mediating forces.

This is what characterize, for example, Dear Jeff Bezos, a one-year performance in which the ‘interface artist’ Johannes P. Osterhoff reflected on the acquisition and control of reading data by Amazon. Whenever Osterhoff set a bookmark on his Kindle, an email containing the book’s title and the current position in the text was automatically sent to Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon. At the same time, the passages were also published in the website bezos.cc and so they became publicly available.

I’d like to conclude my speech by explaining why I don’t necessarily practice what I preach. After all, this presentation is hosted on Google servers. Although I’m profoundly convinced that it’s important to dispute ubiquitous monopolies, I’m also fascinated by the possibility of repurposing platform-centric environments.

Photo booth as presentation software, #selfiestick as pointing device. #TuringCompleteUser pic.twitter.com/7EArn3zMez

— olia lialina (@GIFmodel) January 15, 2015One of the further readings suggested by Dave is Olia Lialina’s “Turing Complete User”. In this essay, she speaks of users “who are challenging, consciously or subconsciously, what [they] can do and what computers can do […].” While researching experimental publishing I stumbled upon several Turing Complete Users. I think it would be incorrect to exclude those only because they take advantage of proprietary platforms or software. Furthermore, Turing Complete Users are often able to highlight levels of mediation and partially escape them.

If we stretch the definition a bit by considering unintended uses of proprietary platforms, a practical example would consist in connecting a series of Google Docs and make them into full-fledged websites. If I’m correct, the first to try this out was the Swedish design studio Konst & Teknik in 2010.

More recently, design studio This Is Our Work, in collaboration with Clement Valla, extended the concept and created a free web template called Binder. Binder adds a “a simple navigation layer on top of an already-existing web format”. To me, its beauty lies in the way it takes advantage of the multiplicity of the Web and in its pseudo-parasitical use of centralized platforms. Made of just a few lines of code, Binder is an exercise of frugality — yet it can accommodate a complex web-app like Google Docs.

That is to say that rich and poor media are not mutually exclusive, but I hope that the latter will be the ones in the driving seat.

Thank you.