Title |

Book, Print, Ink, Paper, Type: Interview with Jesse England |

Author |

|

Date |

Jesse England is an artist and educator “working with contemporary media concerns”. The several media he explores are profoundly diverse: from Iphone covers to prototypal devices able to record moving images on paper. In doing so, he often seems to debunk the linearity of technological progress, as it is conceived by common sense (e.g. book>e-book). In occasion of the inclusion of E-book backup in P—DPA, I asked him some questions about this project and a few others that are in some ways related to the the field of print and publishing.

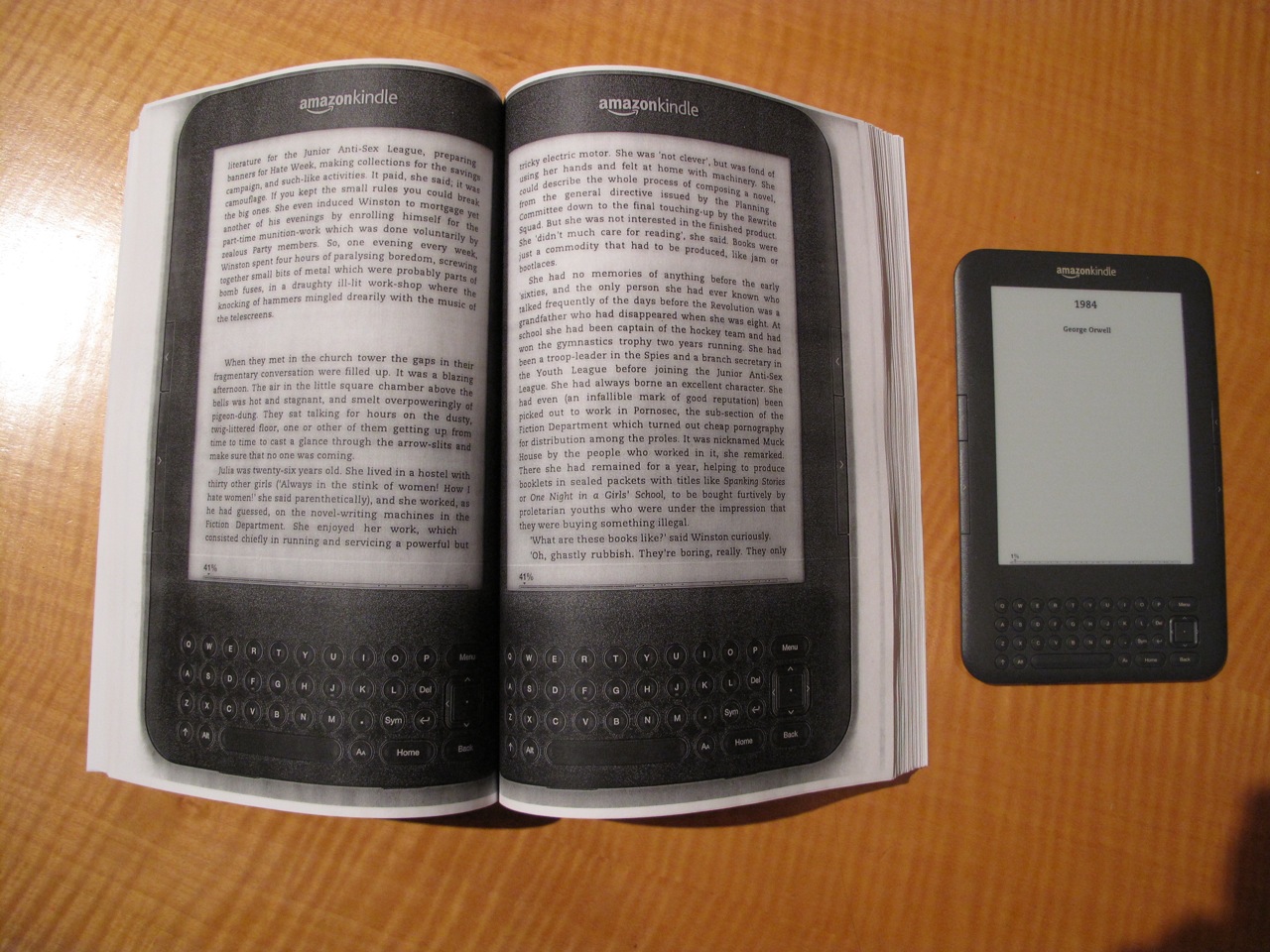

Silvio Lorusso: Jesse, you first realized E-book backup – a physical backup copy of an e-book – in 2012, three years after Amazon removed copies of 1984 and Animal Farm from Kindle devices without asking any permission to the customers involved. What made you address this episode through a work of art?

Jesse England: I wanted to highlight this momentous event in publishing history. I couldn’t have asked for a better criticism of the volatility of e-books than the action taken by Amazon, and I wanted to highlight this weakness with a physical gesture. I was worried that this action would be too late, but when I made it in 2012, the majority of people I’ve spoke to about the 1984 recalling event had no idea that it even transpired. I was glad to spread the knowledge that these e-books could be recalled remotely.

SL: Did you have chances to exhibit E-book backup? If you were asked to, how would you do that? I guess a performance in which you (legally?) photocopy your purchased library would be very powerful…

JE: It was exhibited in three group shows about media-related concerns, atop a librarian’s book pedestal. Viewers were encouraged to touch and examine the book. A photocopying performance would be ideal; In my work, I hope to show how easy it is to defeat such locked media formats.

SL: The piece brilliantly exposes the risks connected to the passage from ownership to access. Do you think this shift will be unavoidable for digital books?

JE: I don’t think so. There has always been a negative or lukewarm response to any new media that impose undue or artificial limits on consumption and sharing, and the workarounds to making a solid personal copy for yourself have always been straightforward. The only way that e-books will be accepted is if an open and relatively universal standard is adopted, and I believe it will happen eventually.

SL: In your work, the printed book acts as a sort of memento of the users/readers’ rights in terms of preservation of knowledge and even control over it. What other roles do you attribute to print and books today?

JE: In addition to those things, books represent an untraceable means of storing and retrieving information under most circumstances. For an individual to buy or borrow a book and read about something without it being noted by Google or their country’s surveillance administration is almost becoming a political act in itself.

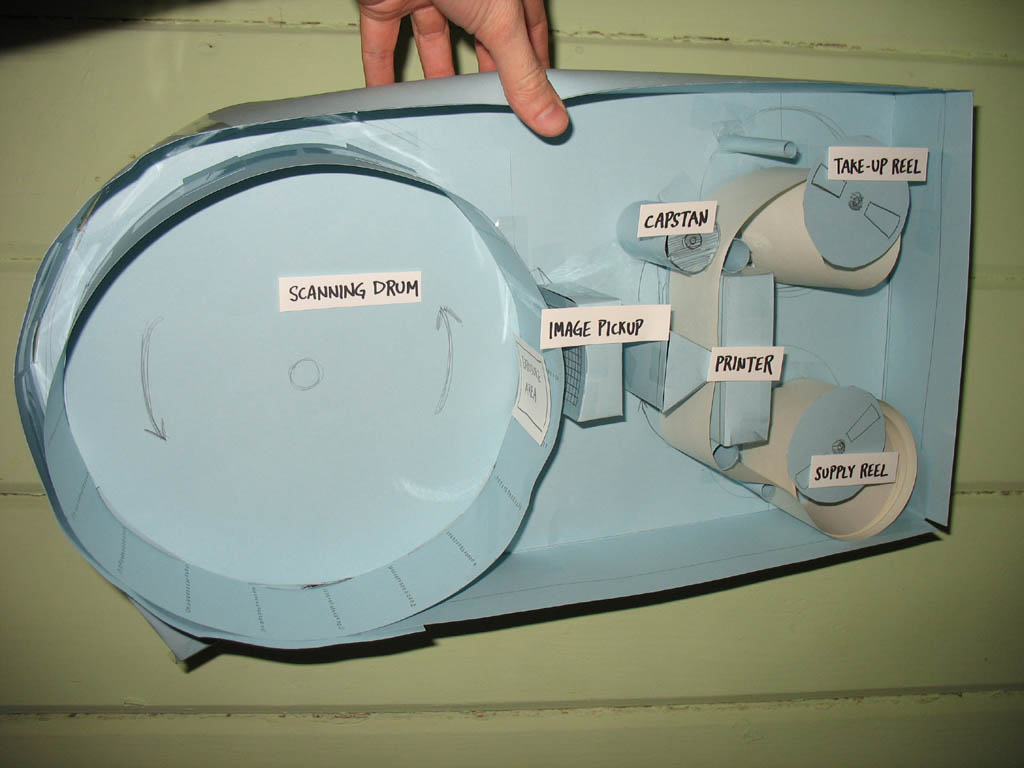

SL: You conceived a system called Paper Movie Process, able to capture moving images on paper rather than film or digital drives. Such system “would survive the aftermath of a nuclear war, with no availability of photo labs or electrical power”. In this perspective, ink and paper return surprisingly to their traditional archival function, in the form of a long scroll. How do you see this project evolving?

JE: Although I got the idea several years ago, I shelved it at the maquette stage because I began to question my urge to document everything; I was a prolific photographer of my own life until I considered the role of the camera as a mask, preventing me from living the moments I was capturing. As the media landscape changes, however, I wish to revisit this project with the ideas of un-networked photography and the drive for media tangibility.

SL: Inkless printing with lasers is another interesting experiment that redefines print through the use of laser cutters and engravers. Have you proposed or accidentally found any application of this concept or similar ones?

JE: The idea of reducing the ingredients for printing down to one consumable element, paper, appealed to me for the simplicity. Although I do not anticipate ink becoming unavailable in the future, the ability to do without an archaic manufactured item for a creative process excites me. Boiling walnut shells for ink is much easier than making your own photographic film, however.

SL: You often highlight significant implications related to specific media by making comparison, sometimes ironic, with older or completely different ones. This reminded me of the “reversed remediation”, an artistic strategy that, in Saskia Korsten’s words, “creates a state of critical awareness about how media shape one’s perception of the world”. Do you think this is an efficient way to build awareness among users? And would you say this is the main goal of your work?

JE: Absolutely. Of course I don’t expect people to photocopy their e-books or listen to their mp3 files through an analog tape filter, for example. Within my work, I hope to highlight what is lost and gained as we transition from one way of seeing (or hearing) to the next. If nothing else, I want people to know that it is indeed possible to defeat artificial limits on media consumption and generation, even through seemingly ridiculous ways.

SL: One of your latest ongoing project is called Learn to write in different fonts. Each week you produce a video-tutorial in which you explain how to conform handwriting to well-known typefaces that are part of the desktop publishing vernacular. Beside the Comic Sans’ hype, do you see digital typography as being an integral part of our cultural landscape?

JE: Typography has always been part of our cultural landscape since Gutenberg, and digital typography has simply increased the accessibility by which one can contribute to that vernacular. Consequently, as people gain greater access to the tools needed to typeset and even create their own fonts, then the emotional attachment involved with typography will surely increase.

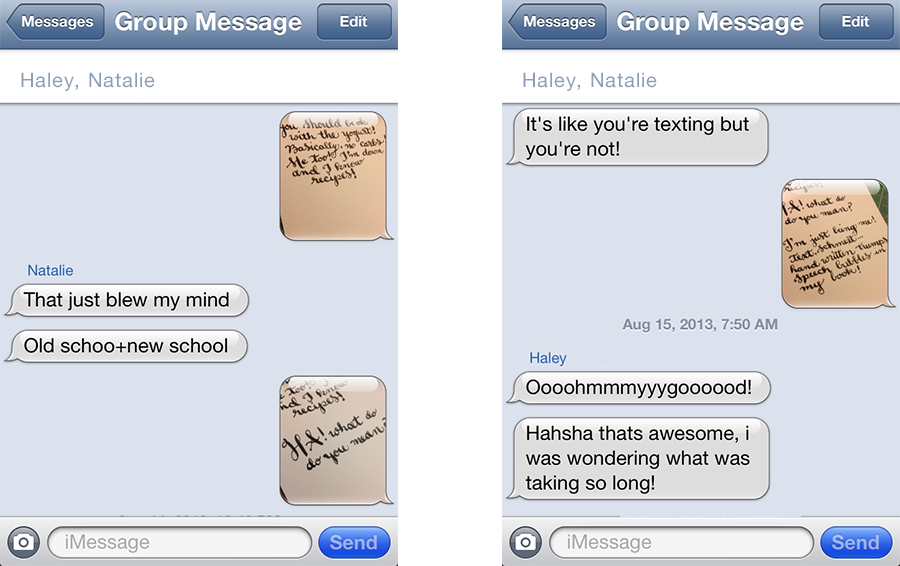

SL: For a week, designer and illustrator Cristina Vanko, replied to the text messages that she received on her mobile phone with pictures of handwritten texts. In this way she “injected” humanity into a fully digital environment. The project looks a bit like the opposite of Learn to write in different fonts, where the man-machine relationship is overturned. Am I right in saying so?

JE: Indeed. Her project seems very much about her own particular handwriting style, which is very beautiful- I did not see any handwritten emoticons, for instance.